Introduction

In the early 1990s, arcades were more than a pastime. They were communities, battlegrounds, and places where reputations were made one quarter at a time. No cabinet commanded more respect—or more adrenaline—than Street Fighter II.

What began as an experiment inside Capcom’s development office evolved into a global phenomenon that resurrected the arcade industry, pioneered competitive gaming, and cemented fighting games as a cornerstone of pop culture.

This is the story of how it all happened—and why it still matters.

From Final Fight to a New Vision

By the end of the 1980s, Capcom had earned acclaim with Final Fight, a beat-’em-up that dominated Japanese arcades. Yet within the company, a few developers were eager to explore a different frontier: the thrill of one-on-one combat.

Akira Nishitani, who would become the project’s lead planner, later explained the origins of that shift:

“The request we got was that people were into the Vs fighting of SF1, even overseas,” he recalled. “So make a Vs game to keep that idea going.”

While the first Street Fighter had intriguing ideas—like special moves triggered by joystick inputs—it was clumsy and physically punishing to play. Early cabinets used pressure-sensitive pads that often broke. Still, the idea of personal duels had potential.

“When we started development, we were no longer in a situation where we didn’t have enough ROMs,” Nishitani said. “So we could really focus on improving the game's characteristics.”

A small team was determined to prove that one-on-one fighting could become a mainstream phenomenon.

Building the Team: The Culture of “More, More”

Nishitani and Akira Yasuda—better known by his nickname, Akiman—broke away from Yoshiki Okamoto’s production group to form their own dedicated unit. Their approach to design was radical: rather than sticking to proven formulas, they embraced a culture of constant experimentation.

“We separated from Okamoto’s team and formed our own team,” Nishitani recalled.

Inside that group, no idea was dismissed outright. Akiman described the atmosphere as relentlessly open-minded:

“You were known as the guy who wouldn’t reject anything. You kept asking for more, more.”

That mantra—“more, more”—became their rallying cry, a reminder to push every concept further.

One of the most crucial early decisions was whether to retain the six-button layout that the first Street Fighter had used. Though it had caused headaches, the team believed the added complexity could set the sequel apart. Nishitani said candidly:

“We had one of the SF1 six-button table cabinets on hand, so we decided to just go with that.”

Reflecting years later, he admitted it wasn’t an easy choice:

“Thinking back on it, I almost wish we hadn’t done it.”

Designing a Cast of Icons

While Final Fight focused on familiar archetypes—street brawlers, thugs, and vigilantes—Street Fighter II aimed for something bolder.

“We had rough drafts for everyone except Ryu and Ken,” Akiman said, “with keywords such as ‘beast,’ ‘military man,’ and ‘sumo wrestler.’”

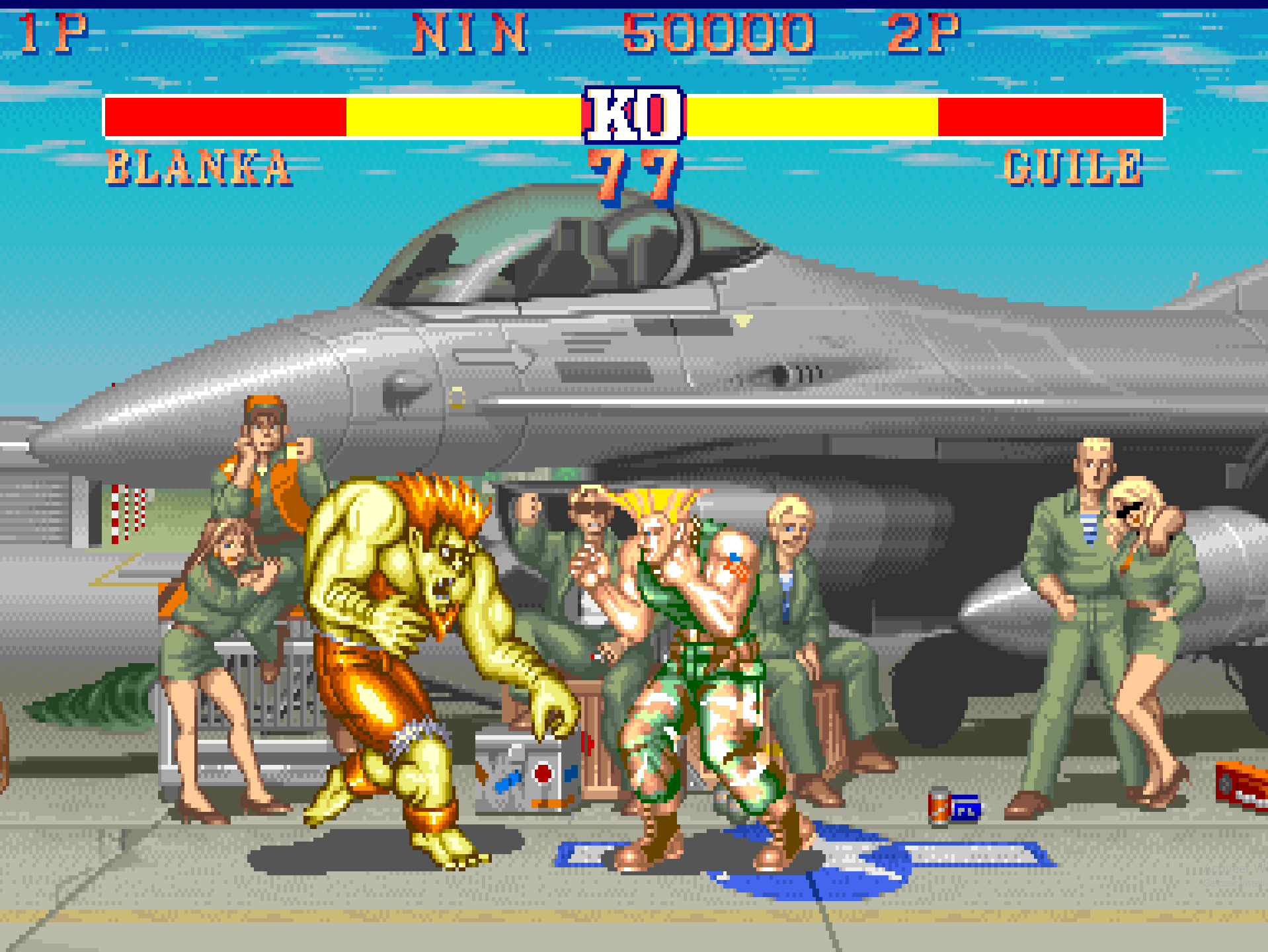

Assignments for each character sometimes came down to chance. Ikusanz, a character artist and lifelong wrestling fan, chose Zangief without hesitation. Erichan, who had just joined the team, picked E. Honda. Pigmon-san ended up with Blanka—a character who almost looked very different.

“At first, Blanka’s skin color was pink, and that was disgusting,” Akiman confessed. “I felt much better after changing it to green.”

For E. Honda, Erichan drew inspiration from Japanese kabuki theater:

“Overseas, people conceal their identities when engaging in street fights,” she explained. “But I thought something like kabuki makeup to really show his pride for Japan would be good.”

The team’s newcomers faced grueling deadlines. Katuragi, assigned Vega late in the process, described working all night on animation frames:

“I was leaving work on time and staying up all night at home doing it. When Akiman-san said to me, ‘You work fast, so it’s not a problem,’ I thought I was gonna die.”

Their collective efforts produced one of gaming’s most iconic rosters: from Chun-Li’s powerful kicks to Guile’s stoic salute.

Innovating the Gameplay

Street Fighter II’s combat was nothing short of revolutionary. Instead of relying on a single attack button, Capcom designed a six-button setup—light, medium, and heavy versions of punches and kicks.

Seth Killian, who later became Capcom’s community manager and a competitive player, described how radical that felt:

“Most games had one button, or maybe crazy games had two buttons. But in Street Fighter, not only were there six buttons but they all did different things…It just seemed infinitely more complicated in a dumb way. Complicated in an exciting way where there was a real reward to investing [time] in the game.”

The system introduced a new level of nuance. Attacks varied depending on distance, timing, and input precision. Originally, the design was meant to recreate chain combos like those in Final Fight, but it evolved into something much deeper: a tactical dance where spacing and anticipation were everything.

Mastering special moves was an obsession. In an era before YouTube tutorials, knowledge spread by rumor and observation. Yoshinori Ono, who would eventually produce Street Fighter IV, described how players became detectives:

“Your neighbor would tell you that he heard that in the town next door some guy was actually doing fireballs on purpose. I would get on my bike and I would go to the neighboring town and I would watch this guy.”

From Obscurity to Obsession

At first, Street Fighter II didn’t explode out of the gate. In Japan, many players were hesitant to challenge strangers. But an inventive arcade owner had an idea: linking two cabinets back to back so that newcomers could play without fear of embarrassment.

As Arcade Mania! recounts:

“The loser-pays model proved so successful that it was adapted not just by Capcom, but by the entire Japanese gaming industry.”

When it hit North America, the response was instant. Jeremy Dunham of IGN recalled:

“I remember huge lines around Street Fighter II the first time I had ever seen it in an arcade and then pretty much every time I went back to play it. That was for a good couple of years.”

According to Replay, Capcom shipped over 60,000 machines worldwide—a stunning achievement that reenergized the arcade business.

A New Kind of Chess

More than just a hit, Street Fighter II became a platform for personal expression. Yoshinori Ono put it best:

“We created a new type of chess. We’ve given players the tools they need to communicate with each other through battle.”

This wasn’t hyperbole. Every character demanded not just mastery of their moves, but an understanding of every opponent’s strengths and weaknesses.

“The variation in characters led to somewhat of a dilemma for gamers,” Ono noted. “They had to master their own character, but also know enough about the other fighters to compete.”

Ryan Cravens, whose father was an executive at Capcom USA, described the phenomenon simply:

“You had your Ken guys and your Ryu guys, but once in a while you’d run into a weird guy, like ‘Okay, who the hell mastered this guy?’”

From Arcades to Esports

No player embodied Street Fighter II’s competitive spirit more than Daigo Umehara. As a teenager, he spent most of his income chasing mastery.

“I saved and scrimped, worked odd jobs, and used my lunch money so I could play,” Daigo said.

On the other side of the Pacific, American players organized grassroots tournaments. Seth Killian described the first gatherings:

“The meeting at the Broadway Arcade wasn’t really a tournament. We said, ‘We’ll all go to the same arcade, and whoever kicks the most ass is the winner.’”

These informal meetups evolved into EVO, the world’s largest fighting game championship.

The Legacy of an Icon

Street Fighter II didn’t just inspire imitators. It set the benchmark for the genre. Toyohisa Tanabe, who helped create King of Fighters, admitted:

“I really respected that game…Capcom has fine-tuned the elements that make fighting games fun, down to the impact of a punch.”

When Capcom revived the series with Street Fighter IV, the challenge was to capture the same magic. Chris Kramer, Capcom’s communications director, recalled the reactions:

“They’d go into our suite and reappear forty minutes later, sweaty and wild-eyed. And the best compliment we heard that whole time we were there was, ‘Wow, this feels just like Street Fighter.’”

Today, Street Fighter remains a living franchise. New installments like Street Fighter V and Street Fighter 6 continue the tradition of precision, creativity, and competition.

Conclusion

More than thirty years later, Street Fighter II’s legacy still thrives in arcades, tournaments, and living rooms around the world. It turned fighting games into an art form—and a cultural language that players of every generation can understand.

Every time you pick up a controller, you’re joining that legacy. And every fireball is a reminder of the game that changed everything.

Sources and Further Reading:

This article draws extensively on firsthand accounts and historical research published in the following works:

- Street Fighter: The Complete History by Chris Scullion (White Owl, 2020)

- Arcade Mania!: The Turbo-Charged World of Japan's Game Centers by Brian Ashcraft (Kodansha International, 2008)

- Attract Mode: The Rise and Fall of Coin-Op Arcade Games by Jamie Lendino (Steel Gear Press, 2020)

- Replay: The History of Video Games by Tristan Donovan (Yellow Ant, 2010)

- The King of Fighters: The Ultimate History (Bitmap Books, 2022)

- Capcom’s official Street Fighter II Developer Symposium (Capcom, 2018)

Want to Go Deeper Into Arcade History?

If the Top 100 left you craving more, dive into the complete stories behind some of the most iconic arcade genres and franchises. These articles explore the rise, innovation, and legacy of the games that shaped arcade culture:

- Donkey Kong’s Rise to Fame: How a Desperate Bet Created a Gaming Legend – The untold story of how Nintendo turned failure into a global icon, launching Mario, Miyamoto, and a new era of arcade storytelling

- What Makes an Arcade Game Great? – A deep dive into the design principles behind the most unforgettable cabinets of all time

- Inside the Metal Slug Legacy: The Developers Who Made It a Classic – How a small team at Nazca crafted one of the most iconic run-and-gun series of all time.

- The Complete History of Mortal Kombat Arcade – How a gritty fighter became a pop culture phenomenon.

- Capcom’s 19XX Series: The Complete History – The vertical shooters that defined a generation of arcade firepower.

- The History of Beat ’Em Up Arcade Games – From Double Dragon to Final Fight, here’s how brawlers ruled the late ’80s.

- The Complete History of Space Shooter Arcade Games – The genre that launched arcades into orbit.

- The King of Fighters Legacy: Inside SNK’s Genre-Defining Saga – How SNK’s 3v3 fighter evolved from a crossover gamble into one of the deepest and most beloved fighting franchises in the world.

- Defender: The Game That Changed Everything – How a risky bet and a radical vision helped redefine arcade design forever.

FAQ

What made Street Fighter II so revolutionary?

Street Fighter II revolutionized gaming by introducing a deep six-button control scheme, unique special moves for each character, and competitive one-on-one gameplay that rewarded strategy and skill. Its precise mechanics and diverse roster set the standard for the fighting game genre and inspired countless imitators.

Who created Street Fighter II?

Street Fighter II was developed by a small team at Capcom led by planner Akira Nishitani and designer Akira Yasuda (known as Akiman). The team also included artists and programmers who had worked on Final Fight and other Capcom arcade titles.

How did Street Fighter II impact arcades?

Street Fighter II revitalized the arcade industry in the early 1990s by attracting huge crowds and sparking competitive play. Its popularity led to over 60,000 cabinets sold worldwide and helped establish arcades as social hubs for gamers.

What are the most iconic characters in Street Fighter II?

Some of the most iconic characters include Ryu, Ken, Chun-Li, Guile, Blanka, and Zangief. Each fighter has distinctive moves and personality, contributing to the game's lasting appeal and cultural impact.

How did Street Fighter II influence esports and competitive gaming?

Street Fighter II laid the groundwork for modern esports by popularizing competitive fighting tournaments. Early grassroots events eventually evolved into major competitions like the Evolution Championship Series (EVO), where players from around the world still compete today.