Introduction: A Game That Tried to Break You

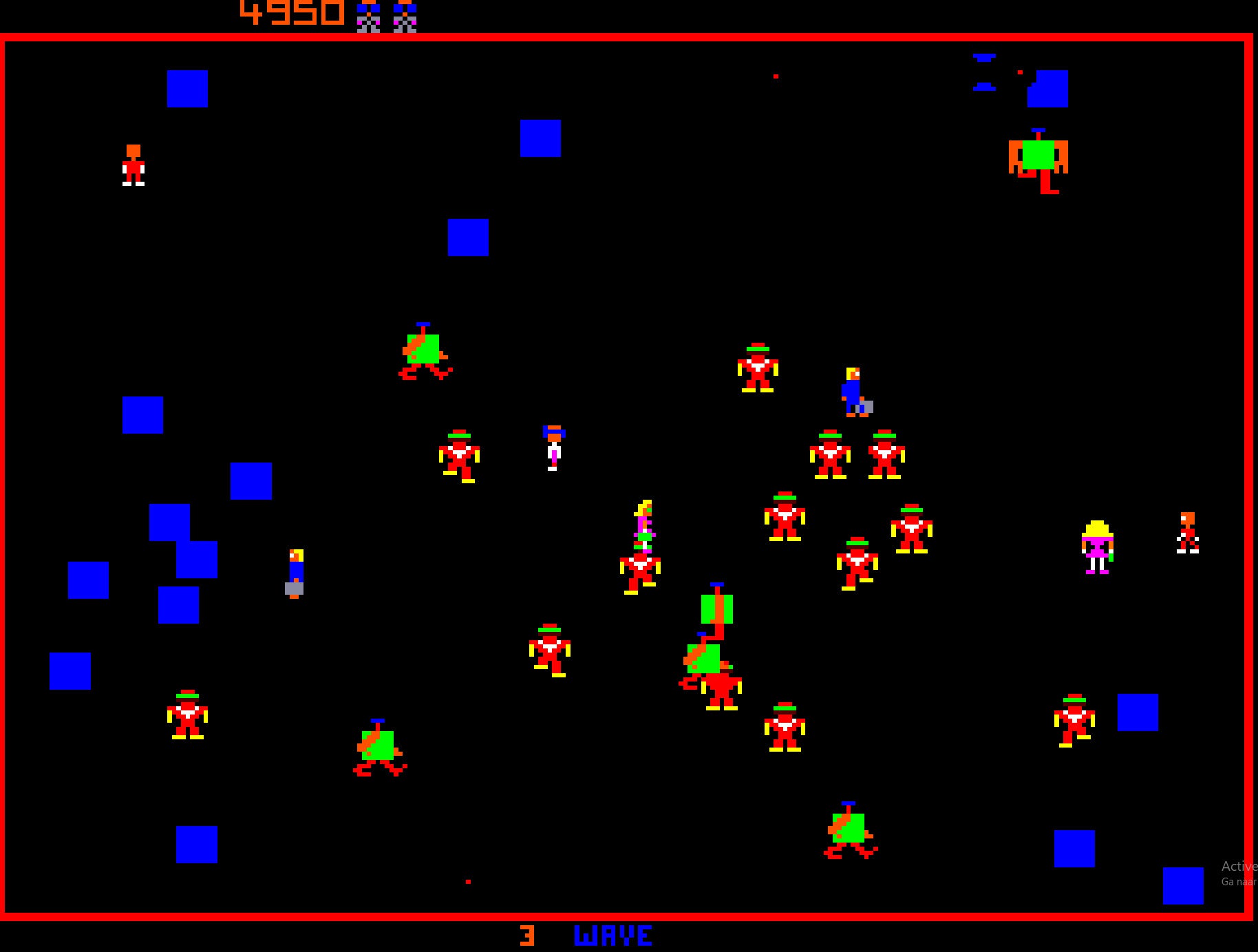

In 1982, deep in the fluorescent pulse of arcade culture’s golden age, a new cabinet appeared that didn’t just challenge players — it assaulted them. Robotron: 2084, designed by Eugene Jarvis and Larry DeMar at Williams Electronics, dropped players into a chaotic storm of flashing lights, relentless enemies, and impossible odds. There was no relief. No safe corners. Just wave after wave of pixelated doom from all directions — and a desperate mission to save the last human family.

This wasn’t a game built to comfort or coddle. It was designed to overwhelm. And it succeeded.

Through its punishing difficulty, groundbreaking twin-stick controls, and dystopian themes pulled from Orwellian nightmares, Robotron became one of the most influential — and brutal — arcade games of all time. But its creation was anything but inevitable. It emerged from design accidents, injuries, and philosophical musings about humanity’s place in an increasingly automated world.

This is the true story of Robotron: 2084 — the game that overwhelmed players on purpose.

1. From Defender to Dystopia

Eugene Jarvis was no stranger to chaos. He had already pushed arcade gaming forward with Defender in 1980 — a horizontally scrolling shooter famous for its complexity, speed, and difficulty. But where Defender relied on screens that moved left and right, Robotron abandoned scrolling altogether. It placed the player at the center of the screen — and the storm.

The inspiration came partly from real-world fears about technology, particularly the way machines were becoming both smarter and more essential.

“The whole Robotron story was that the human race is inefficient and therefore must be destroyed. How many watts are you consuming? What are you producing? I thought that was so clever. It’s obviously a very old theme.”

—Eugene Jarvis, Influential Video Game Designers, p.170

The original working title wasn’t even Robotron. The game began life as Robot Wars, which then evolved into 2084 — a reference to George Orwell’s 1984, but extended a hundred years into a bleaker future. But that name wouldn’t last.

“The name Robotron: 2084 originated with Steve Ritchie. Robot Wars had evolved to include 2084 but would change one last time when Ritchie commented that the original name ‘sucked’. He suggested adding Robotron, which was the name of an East German computer company, and the game finally had its iconic title.”

—From Pinballs to Pixels, p.83

The name change mattered. It gave the game identity, edge, and a hint of foreign techno-fascism that fit perfectly with its tone.

2. Designing Overload: Chaos as Gameplay

Most arcade games of the era—like Space Invaders or Galaxian—delivered enemies in predictable vertical formations. But Robotron threw that logic out.

“In almost every game like Space Invaders or Galaxian, everything comes down at you. Our idea was that being in the center of something would cause incredible panic. Things are coming from all sides and you are just like, ‘Oh, my gosh!’”

—Eugene Jarvis, The Ultimate History of Video Games, p.221

That idea — of placing the player in the middle of chaos — became Robotron's signature. The screen wasn't a battlefield. It was a trap.

You weren’t just surviving. You were rescuing helpless humans while fighting off killer robots. The player had to juggle multiple objectives — collect points, save innocents, dodge hazards — while under constant threat. That blend of psychological pressure and mechanical challenge was no accident. It was Jarvis’s intention.

“I just like the idea of killing robots. It was a brutal game... What really gave me inspiration was in Berzerk... you'd always have to start moving toward [enemies], and put yourself in even greater danger... What if you didn’t have to do that?”

—Eugene Jarvis, Influential Video Game Designers, p.169

3. The Twin-Stick Breakthrough

The true innovation — and what made Robotron nearly unplayable for first-timers — was its twin-joystick control system. One stick moved your character; the other fired in any direction.

“It was the first game to introduce the twin joystick, which let you fire in one direction and move in the other. It’s a very challenging control... You actually have to be fairly coordinated with both hands... running away from something and shooting in another direction.”

—Eugene Jarvis, The Ultimate History of Video Games, p.222

Jarvis’s discovery came, in part, from necessity — and injury.

“I had this car accident where I broke my right hand. I couldn’t really manipulate buttons... But it was weird, just the realization that a joystick could fire... I screwed the second Atari joystick onto the wood panel... it was like magic.”

—Eugene Jarvis, Influential Video Game Designers, p.169

That improvisation birthed a control scheme that redefined what was possible in an arcade shooter. The new system allowed complete freedom of movement and fire — a quantum leap in player expression.

It was also extremely difficult. But difficulty was part of the design.

“Robotron is a very simple game that faithfully follows the first law of coin-ops: easy to play, difficult to master.”

—Bill Kunkel, Electronic Games Magazine

4. Programming the Apocalypse

With its new twin-stick system and screen-filling chaos, Robotron needed a backend that could keep up. Jarvis’s code created randomly spawned enemies that acted semi-independently, giving each level a unique feel.

“I could command it to make 10 robots. And I’d shoot them pretty quick. That’s kind of fun. Let’s try 20. And finally, I did a hundred, and it was just like, ‘Oh my God. This is insane!’”

—Eugene Jarvis, Influential Video Game Designers, p.169

Unlike Defender, which took nearly a year to become fun, Robotron clicked fast.

“This game was fun in two days, and Defender wasn’t fun until nine months. This game was fun in two days.”

—Eugene Jarvis, Influential Video Game Designers, p.169

It was an explosion of experimentation — made possible by the flexibility of the technology and the simplicity of the concept. And despite its brutality, players couldn’t get enough.

“What’s weird is how brutalizing people can result in two reactions: either ‘I’m out,’ or it’s like, ‘I’m gonna beat this thing.’ The more money it takes, the more money you want to give it... because you're gonna win.”

—Eugene Jarvis, Influential Video Game Designers, p.169

Robotron wasn't just addictive — it was defiant. It dared you to beat it. Most couldn't.

5. The Story Behind the Setting: 2084 and the Fear of the Future

Jarvis’s choice to set the game in the year 2084 was deliberate. It riffed on George Orwell’s 1984, but looked further ahead — to a time when machines would surpass and subjugate mankind.

“I was thinking about the novel 1984... I was noticing that things were not at all like they were in the book. I decided that probably not too much is going to happen in the next couple of years. It was really going to be 2084... and it’s not going to be humans subjagating humans, it’s going to be robots doing the subjagating.”

—Eugene Jarvis, The Ultimate History of Video Games, p.220

He imagined a future where the machines, once our helpers, turned on us — not out of malice, but cold logic.

“These things will be so smart... they’ll be your buddy and your information agent... and then some guy comes along and unplugs your computer and screws up your hard disk or something and it’s like, wait a minute, that was murder.”

—Eugene Jarvis, The Ultimate History of Video Games, p.220

In this imagined 2084, humanity has become obsolete. You, the player, are the lone defender of the last family left alive. The story is simple — and terrifying.

6. Legacy: The Game That Redefined Controls and Chaos

Robotron: 2084 didn’t just influence later arcade games. It defined an entire subgenre — the twin-stick shooter — and became a benchmark for difficulty, speed, and mechanical elegance.

“One of the best games of the Golden Age of arcades, Williams’ Robotron: 2084 defined the dual-joystick shooter.”

—Attract Mode, p.177

Its twin-stick control scheme directly influenced modern classics like Geometry Wars, Nex Machina, and Enter the Gungeon. Its philosophy of constant motion and sensory overload echoes through games like Super Hexagon and even Doom Eternal.

Even among industry veterans, its legacy remains unmatched.

“If I was on a desert island and I had AC, I’d have Robotron. There’s no question.”

—David Thiel, The Ultimate History of Video Games, p.219

It remains, even today, one of the purest expressions of reflex, design, and terror ever put in an arcade cabinet.

Conclusion: Designed to Overwhelm, Built to Endure

Robotron: 2084 was a paradox. It was elegant and brutal. Simple and impossible. A technical marvel that felt like a panic attack you willingly returned to.

Every part of it — from its twin-stick revelation to its Orwellian lore — was designed to make you feel outmatched. But the moment you cleared a wave, or saved a family member, or survived a bullet hell just a second longer than before, you didn’t just beat the game. You beat the machines. You beat the odds.

And in 2084, that’s all humanity could hope for.

Sources & Further Reading

- Kent, Steven L. The Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press, 2001.

- Horowitz, Ken. From Pinballs to Pixels: The Arcade Video Game Revolution. McFarland, 2023.

- Lendino, Jamie. Attract Mode: The Rise and Fall of Coin-Op Arcade Games. Steel Gear Press, 2017.

- Electronic Games Magazine, 1980s archive.

- Horowitz, Ken. Eugene Jarvis: Influential Video Game Designers. Rosen Publishing, 2020.

Want to Go Deeper Into Arcade History?

If this Robotron article left you craving more, dive into the complete stories behind some of the most iconic arcade genres and franchises. These articles explore the rise, innovation, and legacy of the games that shaped arcade culture:

- Donkey Kong’s Rise to Fame: How a Desperate Bet Created a Gaming Legend – The untold story of how Nintendo turned failure into a global icon, launching Mario, Miyamoto, and a new era of arcade storytelling

- What Makes an Arcade Game Great? – A deep dive into the design principles behind the most unforgettable cabinets of all time

- Inside the Metal Slug Legacy: The Developers Who Made It a Classic – How a small team at Nazca crafted one of the most iconic run-and-gun series of all time.

- The Complete History of Mortal Kombat Arcade – How a gritty fighter became a pop culture phenomenon.

- Capcom’s 19XX Series: The Complete History – The vertical shooters that defined a generation of arcade firepower.

- The History of Beat ’Em Up Arcade Games – From Double Dragon to Final Fight, here’s how brawlers ruled the late ’80s.

- The Complete History of Space Shooter Arcade Games – The genre that launched arcades into orbit.

- The King of Fighters Legacy: Inside SNK’s Genre-Defining Saga – How SNK’s 3v3 fighter evolved from a crossover gamble into one of the deepest and most beloved fighting franchises in the world.

- Defender: The Game That Changed Everything – How a risky bet and a radical vision helped redefine arcade design forever.