Introduction: The Game That Wasn’t Supposed to Be KOF

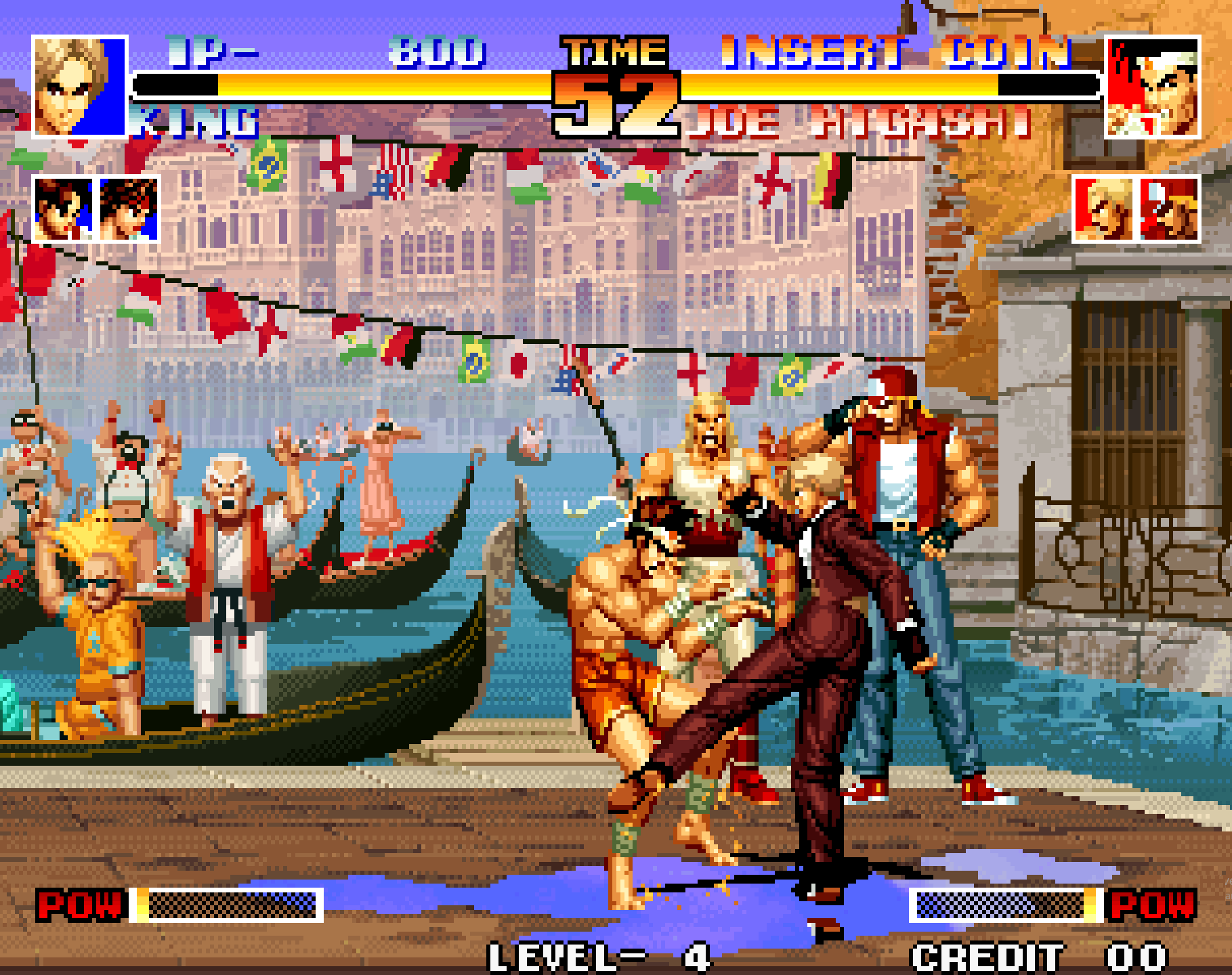

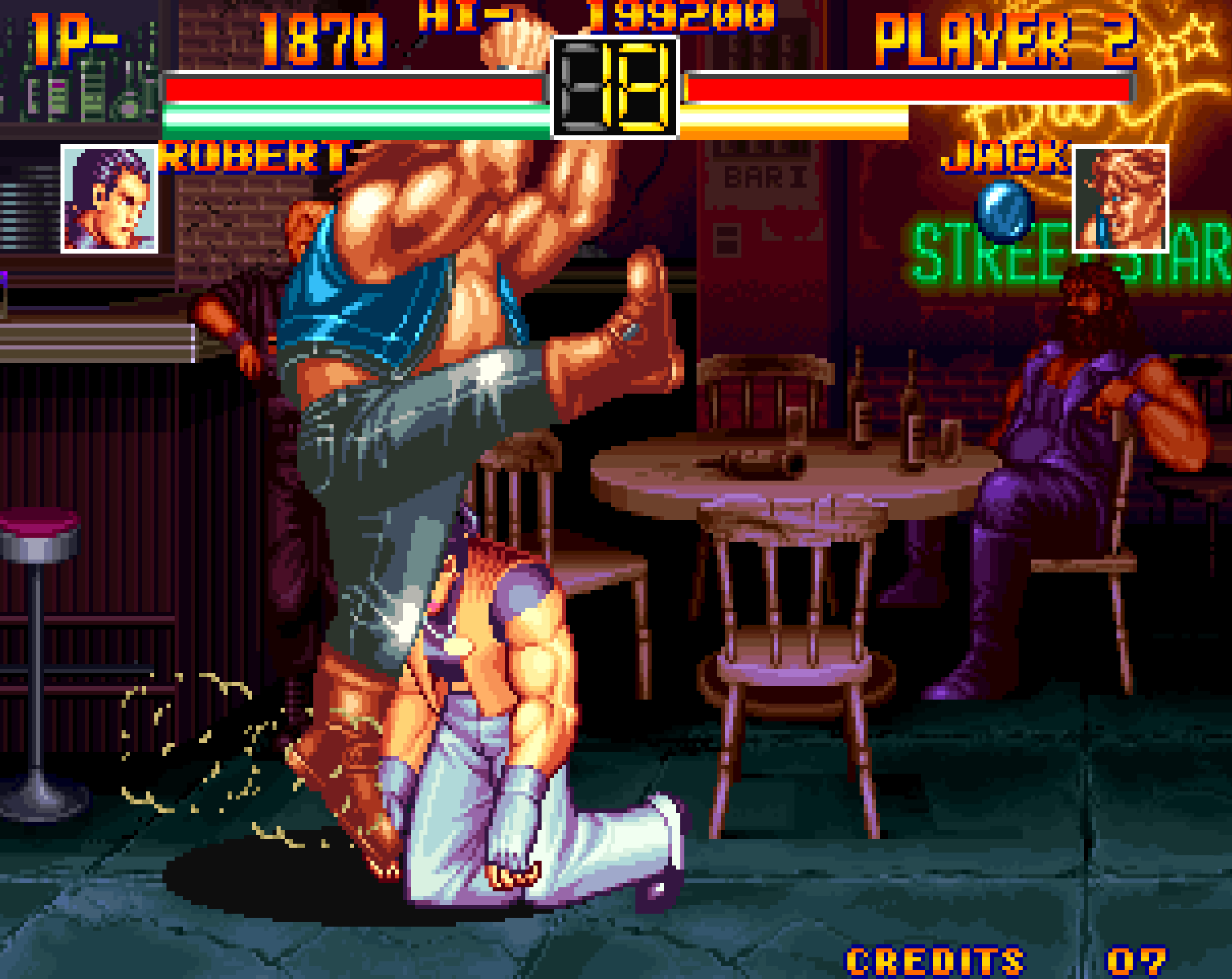

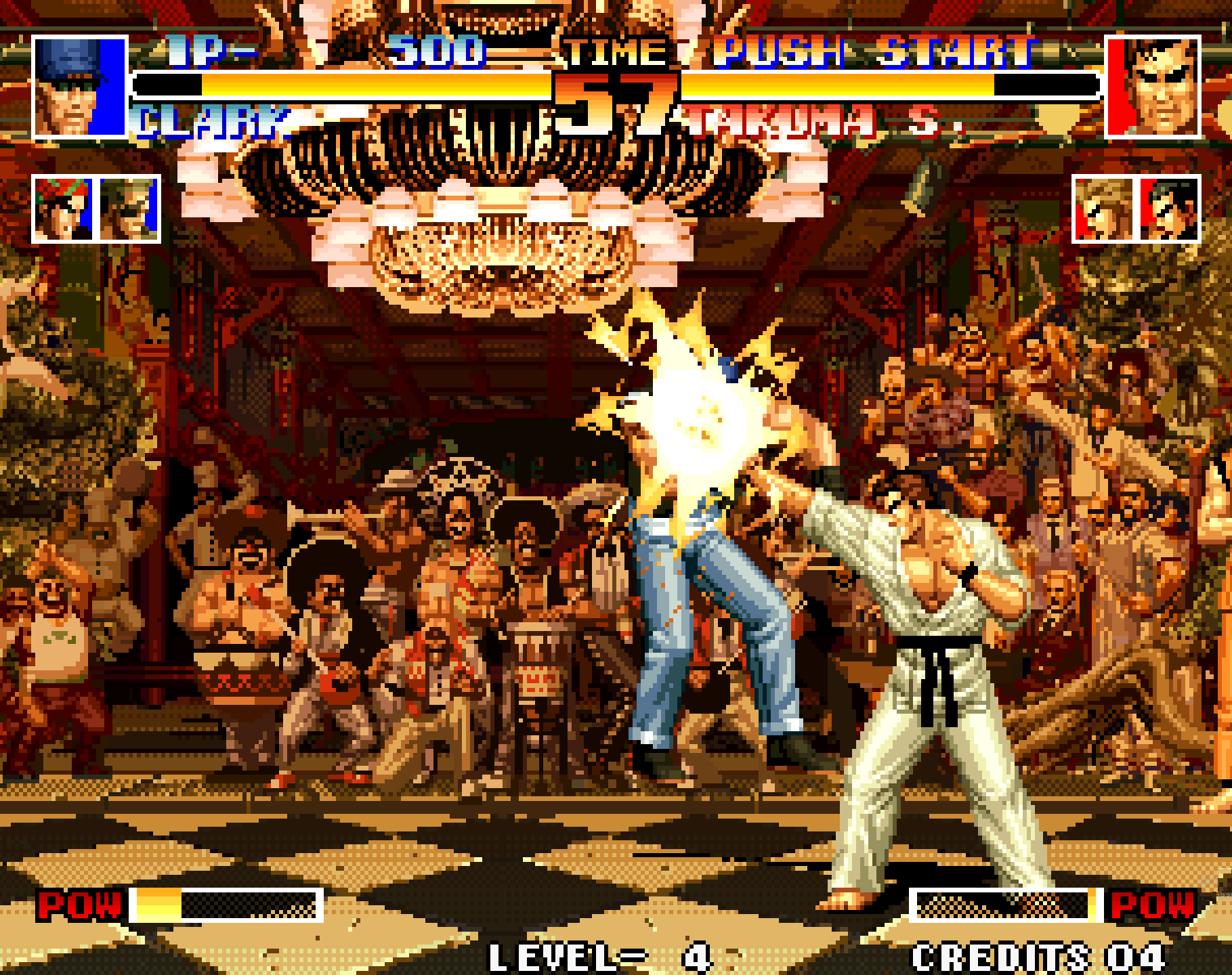

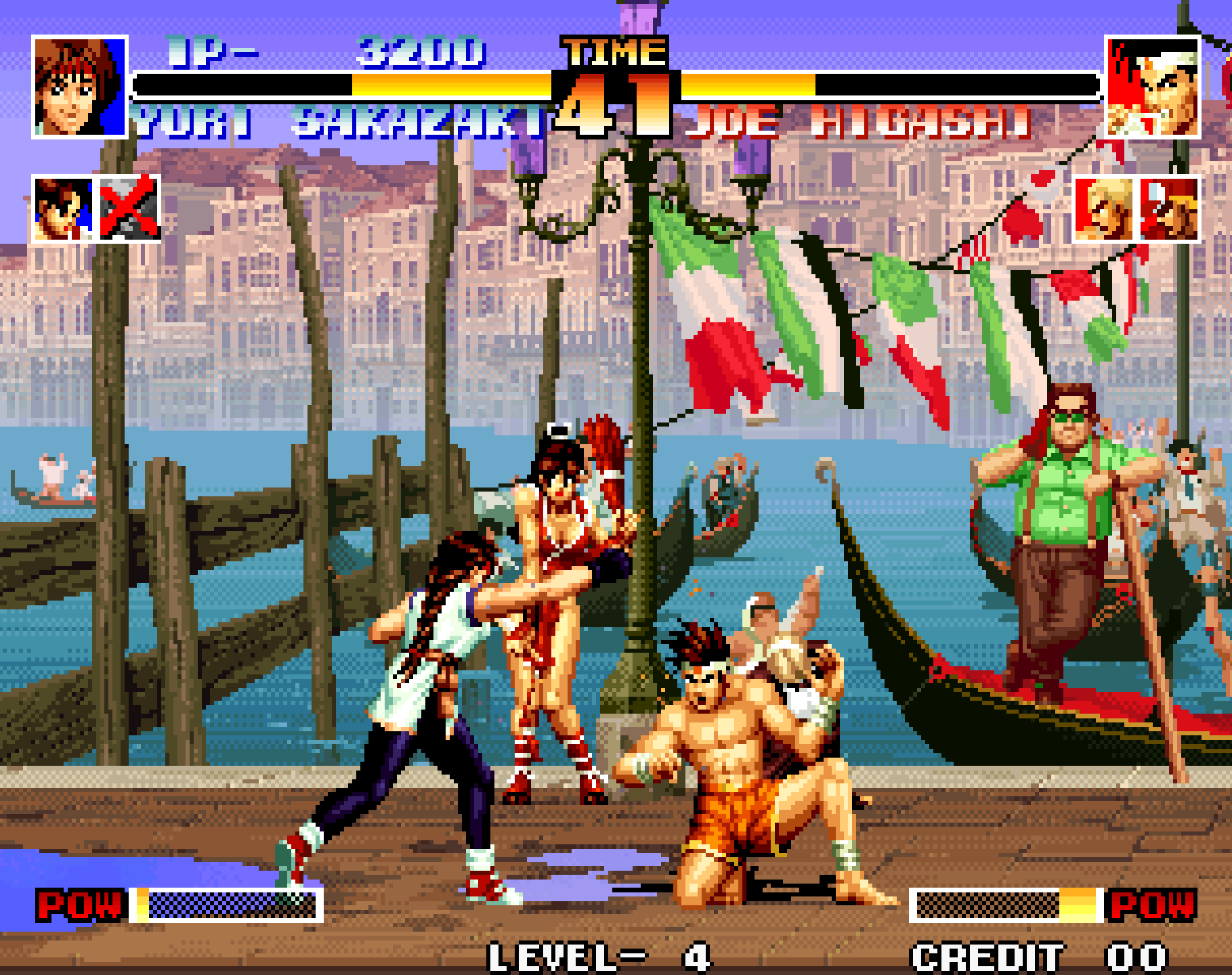

By the early 1990s, arcades were in the midst of a fighting game explosion. Capcom’s Street Fighter II (1991) had triggered a global phenomenon, Mortal Kombat (1992) had become a pop culture lightning rod, and SNK had carved out its own niche with visually rich, mechanically distinct fighters like Fatal Fury (1991) and Art of Fighting (1992).

But even in this crowded landscape, SNK wanted something different — a fighting game that wasn’t just another Street Fighter II clone. The game that would become The King of Fighters ’94 didn’t even start as a fighting game. It began life as a side-scrolling beat ’em up called Dirty Knuckle.

What followed was one of the more unusual development stories in arcade history: a project redirected midstream, a team of mostly untested twenty-somethings given enormous creative freedom, and the birth of a 3-on-3 fighting format that would become one of SNK’s most enduring innovations.

The Roots: Dirty Knuckle and Survivor

When Masanori Kuwasashi first began work on the project, the goal was to rival the appeal of Final Fight.

“I was very excited to work on a game that we envisioned could be a big hit like Final Fight. One of the ideas we came up with was similar to Final Fight. It was similar to Final Fight as a side-scrolling, belt-action game.” — Masanori Kuwasashi, KOF ’94 Director

The project even went through multiple working titles. Toyohisa Tanabe, lead planner on five future KOF games, recalls:

“Yes, Survivor was the name of the project that would eventually became KOF, but even before Survivor it was called Dirty Knuckle. It was a side-scrolling beat-’em-up game like Final Fight, and the idea of working and fighting in teams [originated in] Dirty Knuckle.” — Toyohisa Tanabe

That team-based concept — battling as a group instead of as an individual — was in place from the very beginning. Kuwasashi describes the idea in detail:

“The idea of team battles originated from Survivor, and the idea was that there would be Mafia-like groups from different parts of the world fighting against each other. You played as one, two or three of the main characters and would be fighting against a team of three, in that side-scroller mode. The enemy team would function as the mid-bosses or bosses, in the midst of the waves of henchmen.” — Masanori Kuwasashi

The Pivot: ‘Do This Instead’

When the team presented its beat ’em up plan to management, they didn’t get a rejection — they got a redirection.

“It wasn’t that the title was cancelled. When we presented the planning document to our manager, he said, ‘Well why don’t you do this instead?’ and the direction of the game at that point switched from a side-scrolling action to a 3-on-3 fighting game. Survivor itself never left the planning document stage.” — Masanori Kuwasashi

The timing made sense. Fighting games were dominating arcades, and SNK already had the hardware and expertise to compete.

“I was tasked to make a game like Final Fight and made the planning document for Survivor. However, the industry at the time was seeing an influx of fighting games and I was sceptical that a side-scrolling action game like Survivor could cut through and become a popular hit game in the midst of that wave.” — Masanori Kuwasashi

Tanabe adds that the change wasn’t just about following the market — it was about finding a way to stand out within it.

“As we worked on Dirty Knuckle, the fight games like Street Fighter and SNK’s Fatal Fury and Art of Fighting became really popular and we could see that shift in the industry. So we switched the concept over from a side-scroller to a fighting game. And to have an edge over other fighting games, we kept the concept of fighting in 3-vs.-3 teams.” — Toyohisa Tanabe

A Young, Chaotic Development Team

This new fighting game was entrusted to a team unlike most in the industry: almost all were in their early twenties, with little or no previous game development experience.

“We started out as a small team but by the time we released the master ROM, there were about 60 of us. The team was made of 20- to 25-year-olds with little or no experience in the industry. They were recently-hired young staff on the development team. We had a high percentage of punk folk for a video game development team. Every day was like a Japanese TV Drama from the ’70s and ’80s.” — Masanori Kuwasashi

They also had something rare in commercial development: time and freedom.

“It was chaos. It was a madhouse, we were doing whatever we wanted. There really was no budget or deadline, so we had a lot of freedom.” — Masanori Kuwasashi

Team Battles as a Selling Point

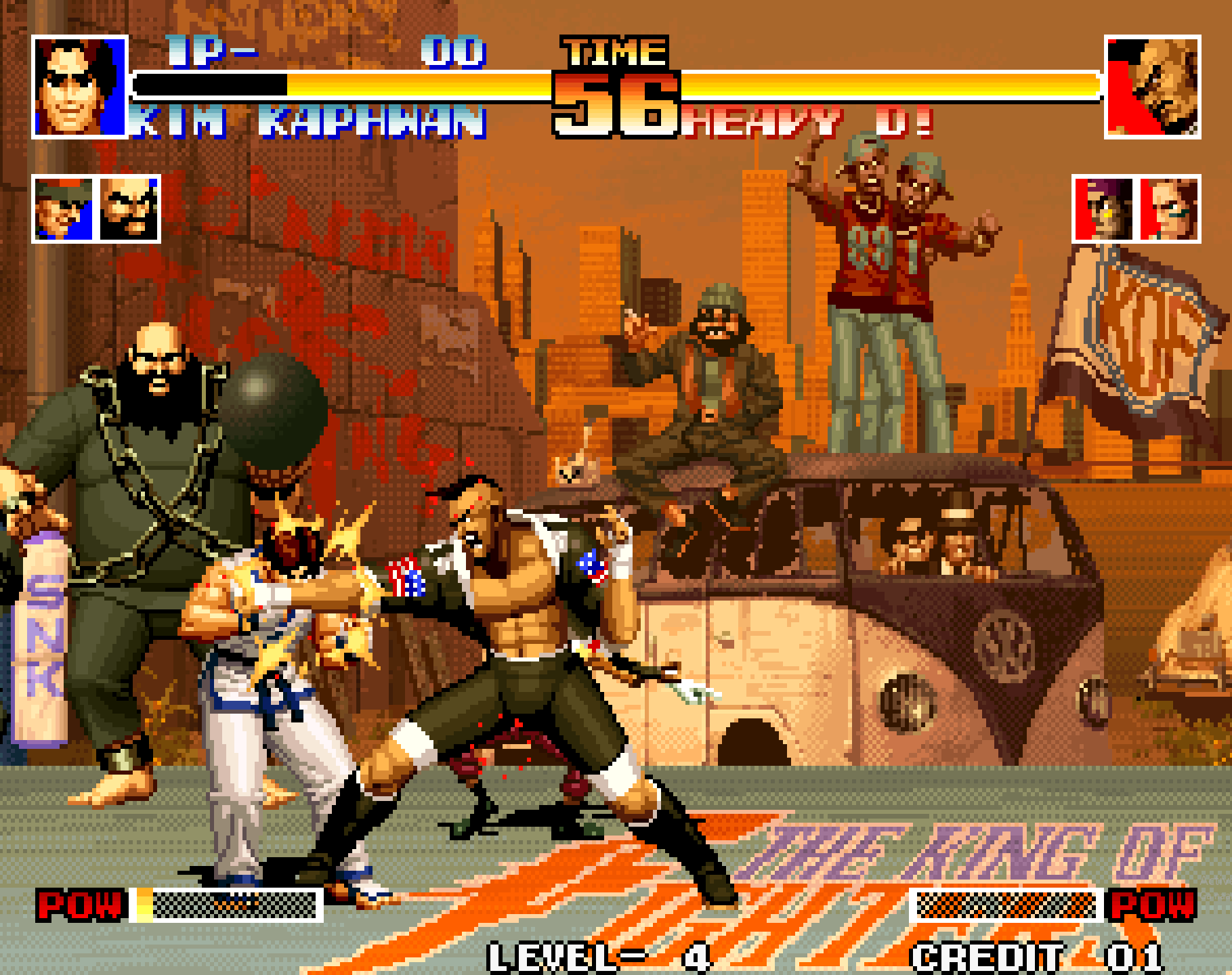

The 3-on-3 team format became KOF’s signature. It was a clear break from the genre’s one-on-one standard, designed to offer players more variety and a new strategic dimension.

“For Street Fighter you’re selecting one character to play out of the eight available, right? For KOF, our idea was to personalise by team rather than a single character. On that team dynamic, it was decided that it would be more interesting to choose out of eight teams rather than six; we wanted to offer as much variety and selection to players as possible.” — Toyohisa Tanabe

It was a bold idea, but the team believed it would be their competitive edge.

“We were also confident in the concept that we could build a personality, or style, around the team, not the individuals. We knew nobody else was doing it so that was our edge and contribution to the genre. We knew 24 characters was a kind of crazy idea, but we were determined to make it happen.” — Toyohisa Tanabe

The Festival of SNK Characters

One of KOF ’94’s most enduring traits — its crossover roster — came from Kuwasashi’s suggestion.

“Once we started making the main character roster, I suggested, why don’t we bring characters in from the wider net of SNK titles and make it a festival and make it more fun? That was my idea.” — Masanori Kuwasashi

It also served a practical purpose.

“It did lighten the pressure on creating original characters, and the reason my supervisor suggested we bring in the assets from the other games to begin with was to lighten the workload.” — Masanori Kuwasashi

Not everyone at SNK was thrilled about borrowing characters from other teams.

“At the time there was a lot of resistance as, after all, we were borrowing characters created by other development teams.” — Masanori Kuwasashi

The Development Struggle

Technical limits were a constant challenge, even with SNK’s powerful NEOGEO hardware.

“Capacity limits definitely limited what we could do, and we completely maximised the capabilities of the NEOGEO.” — Masanori Kuwasashi

Internal feedback during development wasn’t glowing.

“We were told that the stages and characters were too bland. For these reasons the internal reviews were low and we struggled throughout the development up until the release date.” — Masanori Kuwasashi

And the game’s media debut wasn’t the hype-building moment they had hoped for.

“We had announced the release of the game to Gamest as a first reveal and normally the media tries to hype up the game to help get the fans excited about the release. It's not that they said anything bad, but it wasn't as enthusiastic a piece on the game as we had hoped.” — Masanori Kuwasashi

Balancing Under the Clock

Final gameplay tuning was an intense, hands-on process.

“For KOF ’94, most of the game balancing was basically a hands-on trial-and-error ordeal on my part. I balanced most of them by myself in terms of action speeds and strengths of the characters.” — Toyohisa Tanabe

They had only two weeks for the entire roster.

“We only had about two weeks to actually balance the game, less than a day per character.” — Kodoma

Lead programmer Shinichi Shimizu also borrowed from SNK’s other flagship fighter.

“The A.I. patterns for fighting are quite distinct, so I learned and borrowed ideas from the Fatal Fury team.” — Shinichi Shimizu

Release and Realisation

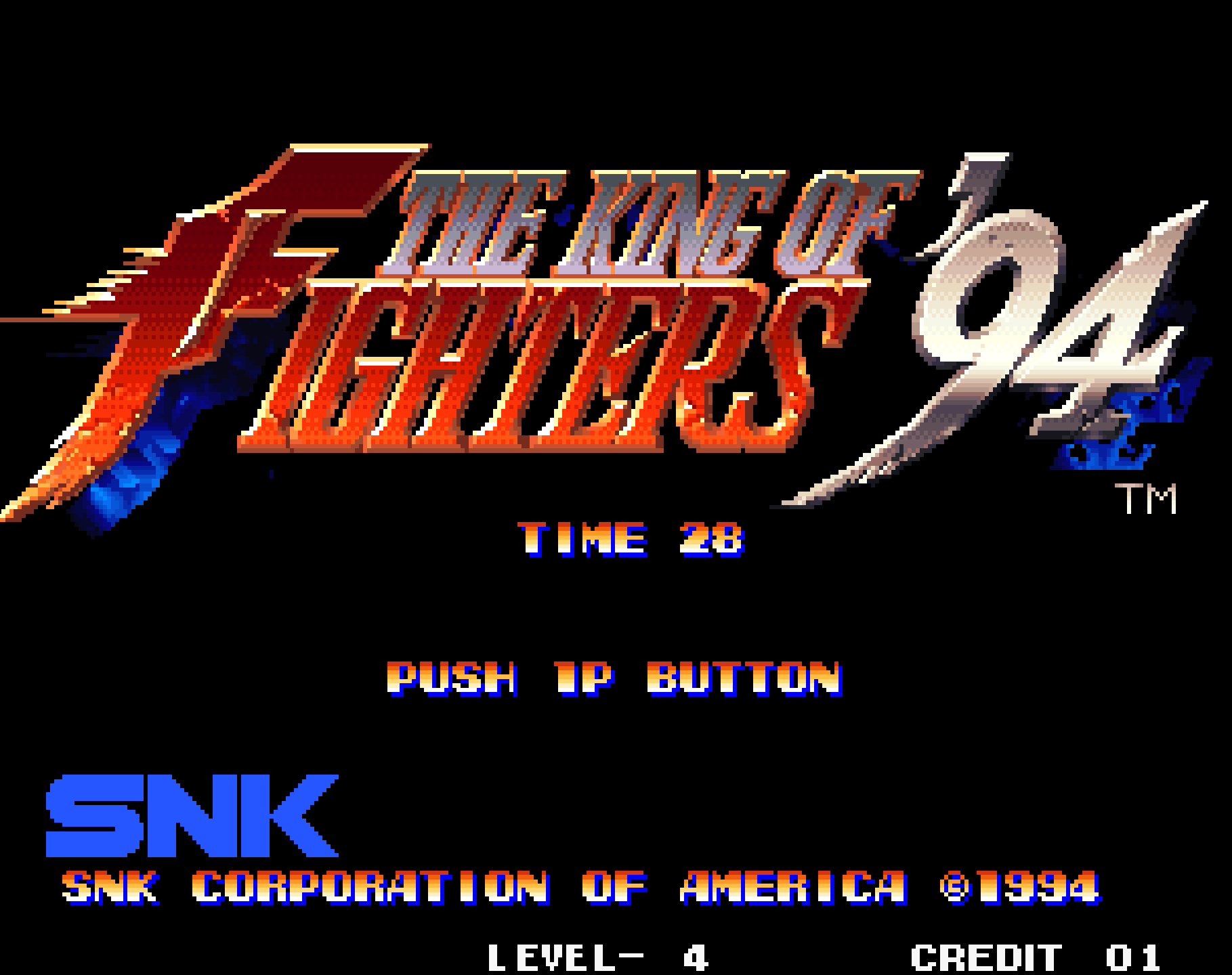

Despite the hurdles, KOF ’94 launched to strong arcade reception. Kuwasashi recalls when he realised it had truly connected with players:

“The point when I could really feel the success of the game, was going to an arcade, and seeing all those people lining up to play the game. That was when the success of the game truly dawned on me.” — Masanori Kuwasashi

Electronic Gaming Monthly was equally impressed:

“SNK's 190+ Meg Beast takes top honours. KOF '94 blew us away for a number of reasons. First of all, it features fighters from other popular SNK games like Fatal Fury and Art of Fighting series all joined together in a unique three-fighter format. Second of all, as a fighting game goes, it is just a phenomenal piece of work. The play control, graphic presentation, and sound quality are all top-notch.” — Electronic Gaming Monthly

Legacy

From its abandoned beat ’em up roots to its bold 3-on-3 battles, The King of Fighters ’94 was a product of a unique moment in arcade history — when creative risks were possible, young developers could lead major projects, and the fighting game genre still had room for major innovation.

Its DNA — crossover rosters, stylish presentation, and fast-paced team mechanics — would define the series for decades. For SNK, it became not just another fighter, but a flagship franchise, standing alongside Street Fighter as one of the era’s defining competitive games.

Sources & Further Reading

- The King of Fighters: The Ultimate History (Bitmap Books, 2022)

- Metal Slug: The Ultimate History (Bitmap Books, 2020)

- Arcade Mania! by Brian Ashcraft (2008)

- NEOGEO: A Visual History (Bitmap Books, 2017)

Want to Go Deeper Into Arcade History?

- What Makes an Arcade Game Great? – A deep dive into the design principles behind the most unforgettable cabinets of all time

- Inside the Metal Slug Legacy: The Developers Who Made It a Classic – How a small team at Nazca crafted one of the most iconic run-and-gun series of all time..

- The Complete History of Mortal Kombat Arcade – How a gritty fighter became a pop culture phenomenon.

- Capcom’s 19XX Series: The Complete History – The vertical shooters that defined a generation of arcade firepower.

- The History of Beat ’Em Up Arcade Games – From Double Dragon to Final Fight, here’s how brawlers ruled the late ’80s.

- The Complete History of Space Shooter Arcade Games – The genre that launched arcades into orbit.

- The King of Fighters Legacy: Inside SNK’s Genre-Defining Saga – How SNK’s 3v3 fighter evolved from a crossover gamble into one of the deepest and most beloved fighting franchises in the world.

FAQ

What was the original concept for The King of Fighters ’94?

The King of Fighters ’94 began as a side-scrolling beat ’em up called Dirty Knuckle. It later evolved into a fighting game with a unique 3-on-3 team format.

Who directed The King of Fighters ’94?

Masanori Kuwasashi served as the director of KOF ’94, guiding the project from its beat ’em up origins through its transformation into a groundbreaking team-based fighter.

Why did SNK switch KOF ’94 from a beat ’em up to a fighting game?

SNK shifted the project to a fighting game after the genre’s explosive popularity in the early ’90s. The 3-on-3 team battle format was kept to stand out from rivals.

Which SNK games did KOF ’94 characters come from?

KOF ’94 featured fighters from Fatal Fury, Art of Fighting, Ikari Warriors, Psycho Soldier, and new original characters, making it a crossover “festival” of SNK titles.

How long did it take to balance The King of Fighters ’94?

According to the development team, KOF ’94’s balancing was completed in just two weeks — less than a day per character — using trial and error and lessons from Fatal Fury.